Navigating Florence.

|

Basilica

di Santa Maria del Fiore (Duomo or Cathedral), begun 1296, comp 1436.

|

|

|

Baptistery,

1059-1128.

|

|

|

Loggia

del Lanzi, Piazza di Signoria.

|

The Canon of Artistic Taste in Florence

The following four artists (Michelangelo, Raphael,

Fra Bartolommeo and Andrea dal Sarto) were considered the greatest in Florence,

but Giotto and Cimabue were barely acknowledged on the tourist trail. Though

Giotto and Cimabue were seen as part of the story of the recovery of the arts

in Italy, their art held little interest for the British visitor. Giotto and

Cimabue’s art was considered “dry” and some commentators refused to consider

then at all. For example, Francis Drake refused to take his account of painting

in Italy further back than the late fourteenth-century. This rejection of the

early renaissance can be seen in the tendency of ignoring even artists before

the late quattrocento and Lorenzo’s patronage of Leonardo, Michelangelo and

Raphael. The author of The Life of Lorenzo di Medici (1795),

William Roscoe was partly responsible for resuscitating taste in the Italian

“primitives” though he wasn’t the first to do so. A number of painters and connoisseurs

were attempting a systematic overview of the evolution of the fine arts from a

“first revival” to the perfection of the quattrocento. These included Thomas

Patch who had authored a Life of Masaccio (1772) as well as publishing

engravings of artists like Fra Bartolommeo. Later, Masaccio and Masolino’s

frescoes in SANTA MARIA DELLA CARMINE feature more in the comments of visitors,

thanks to Reynolds pointing out their influence on Michelangelo in his Discourses. According to Sweet it may actually have been

Patch who drew Reynold’s attention towards the frescoes .when he was in

Florence in the 1750s. Ignorance of the early renaissance partly explains why a

large volume of tourists never recorded anything other than their reactions to

the art in the gallery and Tribuna. In our current small sample, we have the

generous catalogue of works made by Lady Miller and Baron Krüdener, but

Stendhal broke the pattern by giving the galleries a miss on his visit in 1817,

referring his reader to Charles de Brosse. As later editions of the Florentine

guide became more detailed, they tended to include sections on the Italian “primitives.”

As we come to the end of the century greater interest is shown in painters

like, Botticelli, Ghiberti, Ghirlandaio, the Lippi dynasty, and Uccello. By the

nineteenth-century Ghiberti’s BAPTISTERY doors were known, largely thanks to

Michelangelo calling them the “doors of Paradise.

The Duomo, the Baptistery and the CAMPANILE were

definitely on the tourist itinerary. SAN LORENZO was seldom missed by tourists

as it contained the marvels of the Medici Chapel. At SANTA CROCE, people

visited the tombs of Galileo, Aretino as well as Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio,

probably due to Byron endorsing Santa Croce in Childe Harold. There was also rising interest in Dante on the part

of the British. His poetry was translated into English and travellers grew more

interested in his life and work as conveyed through painting. Stendhal was

quite overcome in this church at these funeral monuments, though he doesn’t

mention Giotto’s murals. Determined travellers would visit Santo Spirito to

admire Brunelleschi’s architecture as well as Sta Trinita, thought to be

Michelangelo’s favourite church. Tourists would probably visit SANTISSIMA

ANNUZIATA to see Andrea del Sarto’s frescoes. Apart from Giotto’s Campanile and

the Baptistery, with the famous doors, hardly any other buildings would excite

tourist interest. This “narrowness of vision” was largely due to the guidebooks

which were consulted by visitors to Florence. Richardson’s Account was very important to the English-reading public, but it

covered only the Duomo and San Lorenzo amongst all the Florentine churches in

detail. An example of this narrowing of vision can be seen in the guides of

Edward Wright and Thomas Martyn; though separated by sixty years both limited

their comments to the Duomo, the Ducal gallery and San Lorenzo.

Visitor One: Lady Ann Miller, (1770)

|

|

Pitti

Palace, named after Luca Pitti, 1458, early 20th century photograph.

|

|

|

Hall

of Venus, Palazzo Pitti.

|

|

|

Hall

of Mars, Palazzo Pitti.

|

|

|

Hall

of Saturn, Palazzo Pitti.

|

Visitor Two: Baron von Krüdener, (1786)

|

|

Basilica

of Santissima Annunziata, founded 1250.

|

|

|

Andrea

dal Sarto, Madonna del Sacco (Madonna with the Sack), 1525, Fresco, 191 x 403

cm, Santissima Annunziata, Florence.

|

|

Santi

di Tito, The Vision of St Thomas Aquinas, 1593, San Marco, Florence, oil on

panel, 362 x 233 cm.

|

|

|

San

Marco, consecrated 1443.

|

Visitor Three: Henri Marie Beyle

(Stendhal 1811-24)[4]

|

|

Silvestro

Valeri, Portrait of Henri Beyle (Stendhal) as Consul, Museé Stendhal, Grenoble,

oil on canvas, early 19th century.

|

|

Basilica

of Santa Croce, begun 1294, consecrated 1442.

|

|

|

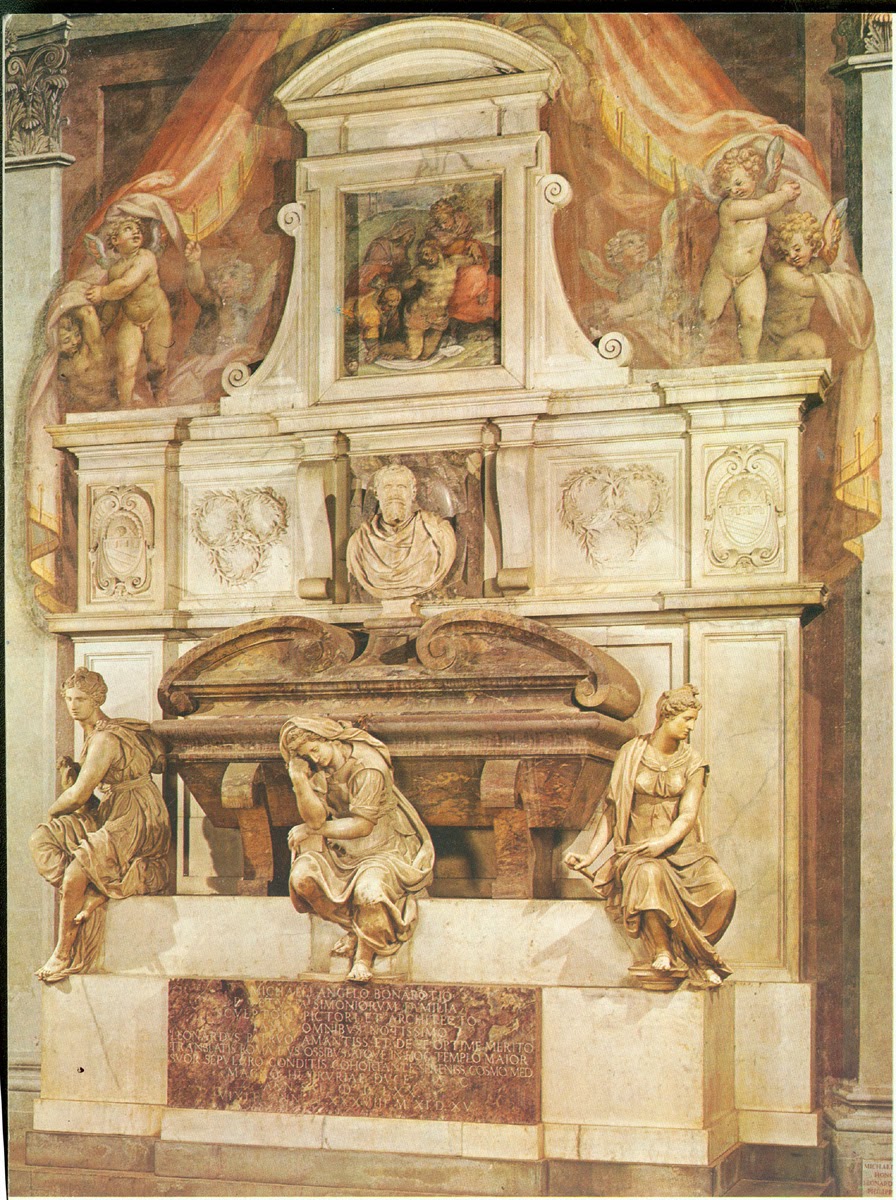

Tomb

of Michelangelo, 1564, (left to right- Architecture, Painting and Sculpture),

Vasari and Battista Lorenzi, and Giovanni dall’ Opera.

|

|

|

View

of Statues Piazza di Signoria: Copy of Michelangelo’s David, Bandinelli’s

Hercules and Cacus and in the distance Giambologna’s equestrian statue of

Cosimo III Medici..

|

Slides

1) Pictorial Map of Florence.

2) Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore (Duomo or Cathedral), begun 1296, comp 1436.

3) Baccio Bandinelli, Prophets, Marble, Duomo, Florence.

4) Baptistery, 1059-1128.

5) Ghiberti, Eastern Door of the Baptistery, 1425-52, Bronze with gilding, 599 x 462 cm.

6) Ghiberti, The Creation of Adam and Eve, 1425-52, Gilded bronze, 79 x 79 cm.

7) Porte San Gallo, begun 1285.

8) Loggia del Lanzi, Piazza di Signora.

9) View of Statues Piazza di Signora.

10) Medici Lion, Loggia del Lanzi, marble, height, (ancient lion, 1.26 m), 2nd century A.D.

11) Baccio Bandinelli, Hercules and Cacus 1525-34, Marble, height 505 cm, Piazza della Signoria, Florence.

12) Benvenuto Cellini, Perseus 1545-54, Bronze, height 320 cm, Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence.

13) Giambologna, Equestrian Statue of Cosimo I de Medici, Piazza della Signoria, bronze, 1598,

14) Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, begun 1246, finished 1360.

15) Masaccio, Trinity, 1425-28, Fresco, 667 x 317 cm, Santa Maria Novella, Florence.

16) Cimabue, The Madonna in Majesty (Maestà), 1285-86, Tempera on panel, 385 x 223 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

17) Church of Santa Trinita, Florence, 12158-80.

18) Domenico Ghirlandaio, Sassetta Chapel fresco cycle, Santa Trinita.

19) Domenico Ghirlandaio Confirmation of the Rule, 1483-85, Fresco, Santa Trinità, Florence

20) Basilica of Santa Croce, begun 1294, consecrated 1442.

21) Silvestro Valeri, Portrait of Henri Beyle (Stendhal) as Consul, Museé Stendhal, Grenoble, oil on canvas, early 19th century.

22) Tomb of Michelangelo, 1564, (left to right- Architecture, Painting and Sculpture), Vasari and Battista Lorenzi, and Giovanni dall’ Opera.

23) Tomb of Galileo, Giovanni Battista Foggini), and figures representing Astronomy (by Vincenzo Foggini), and Geometry (by Girolamo Ticciati), 1737.

24) Giotto, Scenes from the Life of Saint Francis: 6. St Francis before the Sultan (Trial by Fire), 1325, Fresco, 280 x 450 cm, Bardi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence

25) Basilica of Santissima Annunziata, founded 1250.

26) Andrea dal Sarto, Madonna del Sacco (Madonna with the Sack), 1525, Fresco, 191 x 403 cm, Santissima Annunziata, Florence.

27) Pietro Perugino, Assumption of the Virgin, c. 1506, Panel, 333 x 218 cm, Santissima Annunziata, Florence.

28) San Marco, consecrated 1443.

29) Santi di Tito, The Vision of St Thomas Aquinas, 1593, oil on panel, 362 x 233 cm.

30) Santa Maria della Carmine, built 1268, renovated in 16th and 17th centuries.

31) Masaccio, Masolino and Fillipino Lippi, frescoes from the Brancacci Chapel, SMDC, c. 1426-82.

32) Fountain of Neptune, Stoldo Lorenzi, Boboli Gardens, 1565-68.

33) Pitti Palace, named after Luca Pitti, 1458.

34) Hall of Venus, Palazzo Pitti.

35) Titian, “La Bella”, 1536, Oil on canvas, 89 x 76 cm, Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti), Florence.

36) Raphael, Woman with a Veil (La Donna Velata), 1516, Oil on canvas, 82 x 60,5 cm, Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti), Florence.

37) Salvator Rosa, Marine Landscape with Towers, after 1645, Oil on canvas, 102 x 127 cm, Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti), Florence

38) Hall of Saturn, Palazzo Pitti.

39) Fra Bartolommeo, Christ with the Four Evangelists, 1516, Oil on canvas, 282 x 204 cm, Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti).

40) Hall of Mars, Palazzo Pitti.

41) Michelangelo, Doni Tondo, The Doni Tondo (framed), c. 1506, Tempera on panel, diameter 120 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

42) Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio, c. 1625, Oil on canvas, 195 x 147, cm, Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti), Florence.

[1] Letters from Italy, 1776.

[2] Lalande

was an astronomer who published his Voyage

en Italie (2 vols 1765/6).

[3] Voyage en Italie du Baron de Krudener en 1786,

trans. Francis Ley, 1983.

[4]

Stendhal first visited Florence in 1811, and then again after Napoleon’s fall

in 1813. He also spent five months in Florence between 1823-24.Reminiscences of

the city appeared in his Rome, Naples et

Florence of 1817, with a later, fuller revised edition of 1826.

[5]

Stendhal has more to say about Masaccio’s frescoes in his L’ Histoire de la Peinture en Italie of 1811 (Chap XX).